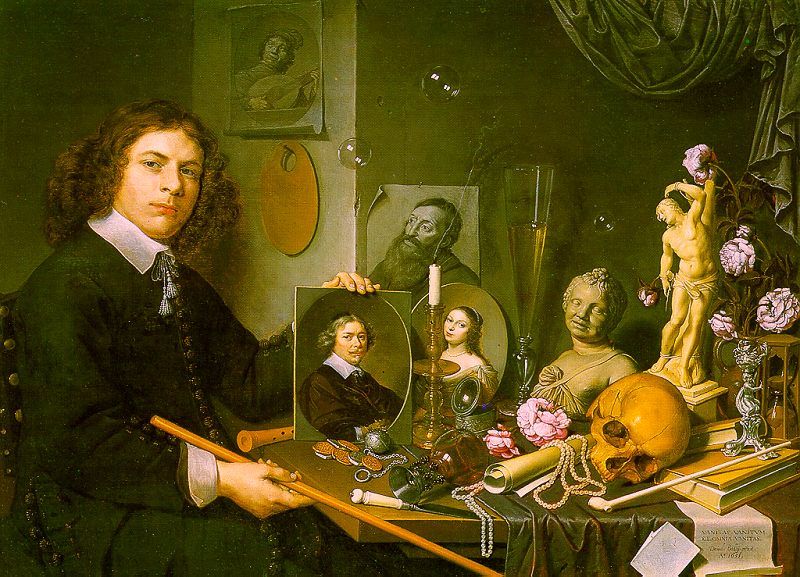

The National Pastime: A bat-and-ball game, called "baseball," but looking an awfully lot like cricket, from the 1767 book, A Little Pretty Pocket-book, essential for every young amateur sporting fellow.

It's Spring in the Northern Hemisphere, and, in our fair United States of America, that means the return of the Grand Old Game, baseball! Opening Day of the Major League Baseball season is nigh, so, here at the Cabinet, we thought we'd take the opportunity to reflect on the amusing origin and peculiar history of that most "American" of sports.

It was Jane Austen, that great promoter of amateur sport, who wrote of one of her heroines in her 1799 novel Northanger Abbey:

It was not very wonderful that Catherine who had by nature nothing heroic about her should prefer cricket, base ball, riding on horseback and running about the country at the age of fourteen to books.

An 1804 watercolor portrait by Cassandra Austen of her sister Jane engrossed in spectating a game of village cricket played near the family home in Bath.

As this rousing quote from the Queen of British Novelists shows, most now agree that baseball evolved from several English bat-and-ball games brought to America's shores by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century colonists. But what of these peculiar pastimes, so foreign to Americans today yet embraced by Albion and much of its former empire?

Foremost among these ancestors of baseball is CRICKET, which originated as a children's game, perhaps related to BOWLS (lawn bowling), during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Beginning in the seventeenth century, however, adults, perhaps as a result of new-found, sheep-induced leisure time, took up the sport. The first reference to cricket being played by adults occurred exactly four hundred years ago, in 1611. Two men from the dragon-infested county of Sussex were brought to court for playing the game on a Sunday instead of attending church. Their fate is unknown.

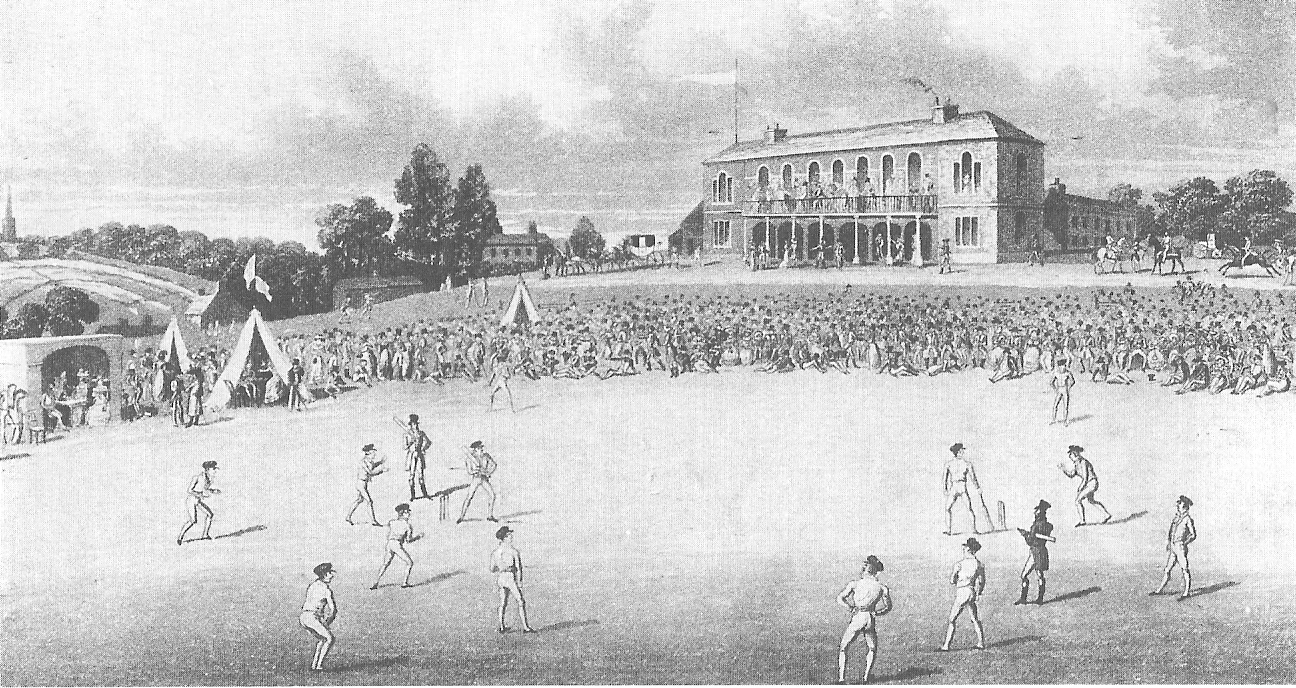

An illustration of a cricket ground at Darnall in Sheffield, England, from around 1820. Not sure about those teepees in the crowd -- mark it up to the influence of George IV's oriental tastes, I guess.

Originally, the bowler ("pitcher") rolled or skipped the ball toward the wicket ("home plate") in the hope of getting it past the batsman ("batter") and knocking down the bails perched atop the wicket stakes ("striking them out"). At first, the cricket bat ("bat") resembled something like a shepherd's crook, but, after the introduction of sidehand and then overhand throwing, it took on a straighter, more recognizable shape. (It is now perhaps most familiar to Americans as an ornamental torture device used in the collegiate Greek system). It remains popular among shepherds, however, who still champion a return to this older, more pastoral form of the game. I will not attempt here to explain all the intricate rules of cricket, nor will I try to define such vital concepts as the Googly, the Diamond Duck, the Chinese Cut, the Nervous Nineties, the Perfume Ball, and the Dibbly Dobbly, for these are sticky wickets indeed to the cricketing novice.

Cricket Bats: The first two examples on the far left date from 1720 and 1750, respectively.

(Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

"A game of Yuletide Rounders at Baroona, Galmorgan Vale," Australia, played on Christmas Day, 1913. Note the player in the back dressed as Father Christmas.

But baseball is not solely a corruption of cricket. Another English bat-and-ball game, ROUNDERS, more closely resembles baseball in form and has been played in England since the sixteenth century. Like the American Game, it includes four bases, nine players to a side, and is organized into innings. Each side takes turns batting and fielding, and a player's successful run around the bases scores a run.

As you might imagine, these similarities struck fear into the hearts of American baseball boosters at the turn of the twentieth century. Many saw it as unpatriotic to admit that the most American of sports was merely a bastardized version of British games. The most ardent champion of the native invention of baseball at was Albert Goodwill Spalding, he of the sporting goods company and magnate of the Chicago White Stockings (today the Cubs) of the National League.

A great debate over the game's ancestry ensued after British-born promoter of baseball Henry "Hanging Harry" Chadwick published a 1903 article tracing baseball's origin from the "good old game of rounders, you know." Spalding, patriotic American that he was, appointed a commission, which reputedly included Samuel "Mark Twain" Clemens and Theodore "Big Stick" Roosevelt, among others, to trace and evaluate the origins of baseball.

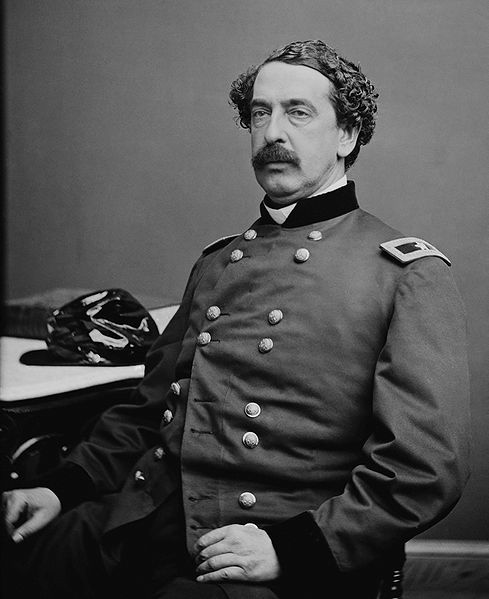

Pioneers of Baseball: Promoter and ball-designer Albert Goodwill Spalding (left), British inventor of the box score Henry Chadwick (center), and aloof Gen. Abner Doubleday (right).

This "Mills Commission" unearthed a 71-year-old man from Denver, Abner Graves, who had witnessed the invention of baseball by Abner Doubleday, later a Civil War general, in 1839, while he was stationed in Cooperstown, New York. (A town best known as home to the author of the Redstocking Tales and High King of the Adirondacks James Fenimore Cooperstown.) Luckily, Doubleday was long dead, and the commission did not attempt to corroborate the old man's tall tale, despite the fact that Doubleday had never even played baseball or even watched a game.

Spalding threw an elaborate and expensive dinner party to celebrate the findings, held at Delmonico's in Manhattan, featuring huge, baseball-shaped souffles and waiters serving with mitts. Committee head Abraham G. Mills, in his address to the audience, summed up the findings of the commission with the curious epigram "NO ROUNDERS. NO ROUNDERS." The unruly and sloshed crowd started chanting Mills' report with increasing urgency, until a melee ensued, during which, among other injuries to those gathered, Henry Chadwick lost his beard and Mills strained his groin. But the commission's findings were accepted as fact, and, in 1939, on the hundredth anniversary of baseball's supposed origin, the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum was opened in Cooperstown.

A photograph of the dinner at Delmonico's celebrating the conclusion of the Mills Commission's investigation, pre-melee.

Well, friends and readers, how can I top that story of ardent yet misguided patriotism? I therefore must now bring this edition of the Cabinet to a close. I hope that, through the stories of the fine English games of cricket and rounders, you have learned something of the origins of our Great Game, be it American or no!

.jpg)