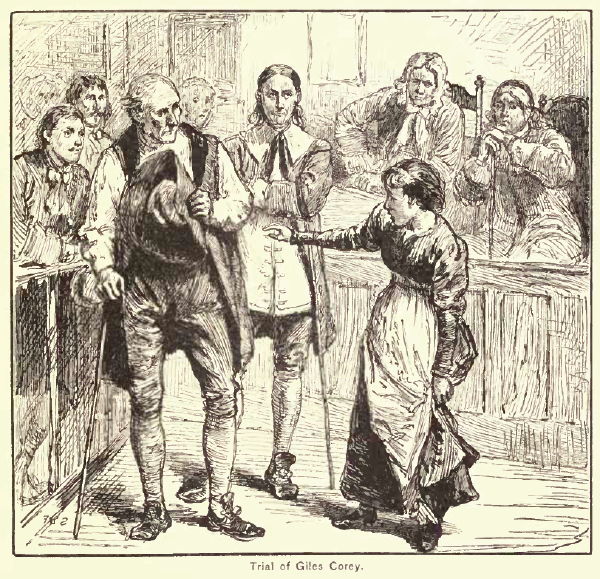

Trial of Giles Corey, an engraving by C.S. Reinhardt from noted old windbag and thanatopsistic William Cullen Bryant's A Popular History of the United States, 1878.

* * *

Giles Corey was a wizard strong, a stubborn wretch was he;

And fit was he to hang on high upon the locust tree.

So, when before the Magistrates for trial he did come,

He would no true confession make, but was completely dumb.

"Giles Corey," said the Magistrate, "What hast thou here to plead

To those who now accuse thy sould of crime and horrid deed?"

Giles Corey he said not a word, no single word spoke he.

"Giles Corey," said the Magistrate, "We'll press it out of thee."

They got them then a heavy beam, then laid it on his breast;

They loaded it with heavy stones, and hard upon him pressed.

"More weight," now said this wretched man. "More weight!" again he cried;

And he did no confession make, but wickedly he died.

* * *

This anonymous early eighteenth-century ballad concerns Giles Corey (1611-92), a victim of the infamous Salem witch trials of 1692-3. While most convicted Salemites were hanged, octogenarian Corey has the special distinction (privilege?) of being the only one punished by being pressed to death.

Ann Putnam, "Have No" Mercy Lewis, and Abigail Williams accused Corey of witchcraft in April 1692. Putnam alleged that the specter of Corey visited her and asked her to write in the Devil's Book (coincidentally some of your Humble Author's favorite bedtime reading). She later claimed that a spirit who'd been "murthered most foul" by Corey also appeared to her. It would seem that the "dread Wizard" Corey's hologramic avatar had gotten around, because other girls subsequently relayed tales of similar spectral pestering that confirmed Putnam's accusations. Fellow supposed practitioner of witchcraft Abigail "Leviathan" Hobbes confessed in court that Corey was a warlock on April 19. Stubborn old Giles, though, refused to enter a guilty or not guilty plea, and was gaoled for several months.

When the court sat again in September, Corey again remained mute. So, the Oyer and Terminer brought out the big guns: pressing, the prescribed punishment for refusing to plea. This piene forte et dure ("hard and forceful punishment"), not to be confused with the later piano forte, called for the prisoner to be stripped of their clothes and made to lie on the ground. Heavy boards were laid over them, and rocks were piled on the wooden planks, increasing in weight until the prisoner confessed. The Massachusetts Bay Colony legal code called for the prisoner "to be laid on his back on the bare floor, naked, unless when decency forbids; that there be placed upon his body as great a weight as he could bear." He must "hath no sustenance, save only on the first day, three morsels of the worst bread, and the second day three droughts of standing water, that should be alternately his daily diet till he died, or, till he answered."*

Ann Putnam, "Have No" Mercy Lewis, and Abigail Williams accused Corey of witchcraft in April 1692. Putnam alleged that the specter of Corey visited her and asked her to write in the Devil's Book (coincidentally some of your Humble Author's favorite bedtime reading). She later claimed that a spirit who'd been "murthered most foul" by Corey also appeared to her. It would seem that the "dread Wizard" Corey's hologramic avatar had gotten around, because other girls subsequently relayed tales of similar spectral pestering that confirmed Putnam's accusations. Fellow supposed practitioner of witchcraft Abigail "Leviathan" Hobbes confessed in court that Corey was a warlock on April 19. Stubborn old Giles, though, refused to enter a guilty or not guilty plea, and was gaoled for several months.

Giles Corey's Punishment and Awful Death, from Henrietta Kimball's Witchcraft Illustrated, 1892. (I'm trying to resurrect the publication of this magazine, if you'd like to contribute.)

When the court sat again in September, Corey again remained mute. So, the Oyer and Terminer brought out the big guns: pressing, the prescribed punishment for refusing to plea. This piene forte et dure ("hard and forceful punishment"), not to be confused with the later piano forte, called for the prisoner to be stripped of their clothes and made to lie on the ground. Heavy boards were laid over them, and rocks were piled on the wooden planks, increasing in weight until the prisoner confessed. The Massachusetts Bay Colony legal code called for the prisoner "to be laid on his back on the bare floor, naked, unless when decency forbids; that there be placed upon his body as great a weight as he could bear." He must "hath no sustenance, save only on the first day, three morsels of the worst bread, and the second day three droughts of standing water, that should be alternately his daily diet till he died, or, till he answered."*

During the course of two days, so the story goes, Corey was asked three times to plead innocent or guilty to witchcraft. Each time he replied, "MORE WEIGHT!" and a new load of New England's famous soul-crushing fieldstone was added to the growing cairn. Finally, at "about noon...Corey was pressed to death for standing mute; much pains was used with him two days, one after another...but all in vain."** Because Corey did not plea, he died with full possession of his estate. Some have written this motivated Corey to stay silent, because the convicted had to forfeit their property to the colony, but the reality such a law has been discounted. In any case, perhaps Corey's endurance was not solely the result of an iron will, but was the action of a father looking after the security of his progeny, and an iron rib cage.

Henry Wadsworth "Old Firesides" Longfellow, nineteenth-century celebrator and hagiographer of Corey and other obscure colonial worthies.

Giles Corey's story had a surprisingly enduring afterlife. The sentimental old fool/poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a play, one of his New England Tragedies, Giles Corey of the Salem Farms, about the stubborn Salemite. Longfellow's Corey justifies his actions to his bosom-pal Richard Gardner, saying:

I will not plead. If I deny, I am condemned already, in courts where ghosts appear as witnesses, and swear men's lives away. If I confess, then I confess to a lie, to buy a life which is not a life, but only death in life. I will not bear false witness against any, not even against myself, whom I count least.Compelling stuff in the old nineteenth-century melodramatic tradition, I say! As Corey dies, Longfellow puts these words in his mouth: "Here is my body; ye may torture it, but the immortal soul ye cannot crush!" Although an unexpected burst of King-James-style eloquence from a man being pressed to death, it is, I think, a fitting and inspired pun, courtesy of the Bearded Bard of Boston.

An illustration by Howard Pyle of an upright Corey, from Giles Corey, Yeoman

Another play about Corey, Mary Eleanor Wilkins Freeman's Giles Corey, Yeoman, appeared in 1893. Freeman's characters are duly impressed by Corey's fortitude, even if it is drawn from Old Nick. "Truly such obstinacy is marvellous!" one magistrate remarks, in such an "unlettered clown" and "old tavern-brawler." Like Longfellow, Freeman portrays Corey as a principled man of good New England stock, presager to the region's great reformers and abolitionists of the nineteenth century, of whom only a few were brutally pressed to death by New England field stone.

Corey also turns up in gravelly-voiced Marilyn Monroe beau Arthur Miller's famous play The Crucible (1953) -- as seen in the clip on the right from the 1995 movie. Although John Proctor, played by Miller son-in-law Daniel Day-Lewis in the film version, is the real star of the play, Corey puts in a brief but memorable performance. I'm sad to say, though, that neither the stage nor screen performances include any full-frontal nudity.

Well, Courteous Readers, the end of the Ballad of Giles Corey draws nigh. I hope this Puritan's moral resilience has inspired, or at least that his tale has amused. Until next time, the Cabinet is closed.

Well, Courteous Readers, the end of the Ballad of Giles Corey draws nigh. I hope this Puritan's moral resilience has inspired, or at least that his tale has amused. Until next time, the Cabinet is closed.

________________________________________________________

* I'm sorry to dash your hopes, but this punishment was not common in seventeenth-century New England, and Corey was the only person in colonial America to be pressed to death in this manner. This, of course, does not include the unfortunate printing press deaths connected with Boston resident Benjamin Harris. Look up, though! Its use was more widespread in Olde England, last employed in the 1740s.

** From the diary of Samuel Sewall, a Salem witchcraft judge, early abolitionist, merchant, Harvard grad, prolific scribbler, and an all-around a real Mensch.

No comments:

Post a Comment