The February 28, 1693/4 issue of the Athenian Mercury, chock-full of inspired questions, sage advice, and unnecessary capital letters.

Ever wonder how Dear Abby, Dear Prudence, Dolly Parton in Straight Talk, or your favorite Agony Aunt got their start? Wonder no more! for today I bring you the story of the seventeenth-century periodical the Athenian Mercury, the first advice column, and its half-crazed, half-genius impresario, John Dunton, and his gang of merry advisers.

Isaac D'Israeli, father of Benjamin Disraeli, called Dunton a "cracked-brain scribbling bookseller, who boasted he had a thousand projects, fancied he had methodized six hundred, and was ruined by the fifty he executed." But among those myraid doomed projects was a lump of figurative journalistic gold! - The Athenian Mercury.

Dunton, sometime denizen of London, called his brain-storm for an advice magazine scheme his "queſtion-answer project." In 1690, he recruited three of his acquaintances, Richard Sault, Samuel Wesley, and "Dr. Norris" to form the Athenian Society. In the pages of the Mercury, the Society would be spoken of as a real club with exclusive membership and regular meetings, in the manner of the Lunar Society (of Birmingham) or the Royal Society (of London for Improving Natural Knowledge). In point of fact, it was just a front for the editors and contributors to the magazine to give them advice-doling cred. Dunton later asserted the membership of the Athenians grew to twelve members, but most of his fellow bookmongers, magazineers, and publishers knew that this claim was just another of Dunton's "damn'd lunatickal lies."

A depiction of a meeting of the Athenian Society, including the four real members and twenty-two phantasmal members. Meetings could get unruly and sometimes resulted in an alcohol-fueled and mob-induced hanging of one of the aforementioned members (see middle panel above). From Charles Gildon's pseudo-history The History of the Athenian Society (1692).

Dunton took out an advertisement to solicit questions for the first run of issues:

All Persons whatever may be resolved gratis in any Question that their own satisfaction or curiosity shall prompt 'em to, if they send their Questions by a Penny Post letter to Mr. Smith at his Coffee-house in Stocks Market in the Poultry, where orders are given for the reception of such Letters, and care shall be taken for their Resolution by the next Weekly Paper after their sending.The Mercury was published twice weekly. The first issues were called the Athenian Gazette or Causistical Mercury, but Dunton quickly contracted the name to Mercury, as to not anger the formidable editors of the London Gazette, then as now the official organ of the English/British/UK government.

John Duntons. Notice the growth of Dunton's wig as he aged.

(Although perhaps the one on the left is a fake, as it refers to a "M.r Iohn Dvnton,"

the dead minister of Aston Clinton, certainly not one of our Dunton's many professions.)

Richard Sault took on the questions relating to maths. Sault was the author of popular titles like A Treatise of Algebra (1694) and a translation from the Latin of Aegidius Strauch II's Breviarium Chronologicum (1699). He also headmaster'd a mathematick school near London's Royal Exchange.

Samuel Wesley, as a clergyman and moonlighting poet, advised on questions of a theological or metaphysical nature. He also happened to be Dunton's brother-in-law.

The fourth (real) member of the Society was the shadowy figure Dr. (John) Norris. Not much is known of his involvement beyond that he tackled questions of a medical or pseudo-scientific nature, and refused compensation for his advising services.

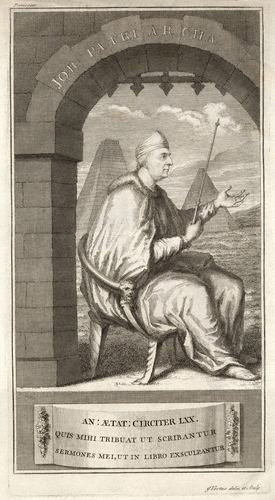

The Reverend Samuel Wesley, Athenian Societitian and father of the Wesley Boys. On the right Wesley can be seen holding his riding crop in preparation for one of his frequent meditative camel rides 'round the pyramids (now demolished) at St. James's Park.

Poultry Street, London, where Dunton founded his multimedia empire, as it appeared in 1697.

[Courtesy: www.flickr.com/photos/markhillary/3261154012/]

But what of the questions themselves? They spanned the length and breadth of Human Curios'ty. The answers, though sometimes clever fictions and dark-stabs, were often informed by the latest in scientific, theological, and common-sensical scholarship. Below are some questions culled from the rag-paper pages of the Mercury:

What's the original cause of the Gout?

Whether stones are porous?

Pray Gentlemen, what is the Cause of Suction?

What's Love?

Which of the five Senses is the most Noble?

[A: Sight is the most Noble, Feeling more Useful.]

Whether Prince Meredith of Wales Discover'd the Indies before Columbus, as some Histories relate?

Is't possible for an Estate to prosper, which is gotten by selling lewd and vicious Books, or can he be a good Man that does so?

Why a Person cannot rise from his Seat, unless he first either bend his Body forward, or thrusts his Feet backwards?

How can a man know when he dreams or when he is really awake?

Many of these continue to baffle our greatest twenty-first-century minds. Indeed, what is the cause of Suction?

What became of of our Athenian worthies after the Mercury ceased publication in 1697? In 1704, Dunton put together a three-volume compilation of the best of Mercury questions and answers, The Athenian Oracle (Although it is so long, and poorly edited, that this author doubts that Dunton did much culling.)

Richard "The Methodizer" Sault had, in 1700, removed himself to Uni. of Cambridge to profess the beauties of algebra. As is the case with most scholars, he died in great poverty in May 1702, despite being "supported in his last sickness by the friendly contributions" of his fellow professors.

Samuel Wesley died in 1735, but not before siring nineteen children, including those twin evangelical dynamos, John and Charles Wesley, founders of Methodism. He also wrote a lot of weird poetry.

An engraving of the newsroom of the Athenian Mercury, as it appeared in 1691. Notice Dunton, sitting at a table in the back, preparing to open a submission from a curious reader with his red-hot letter opener.

After 1697, John Dunton's achievements were, according to a biographer, marked by a “diminishing sense of responsibility and reality" earning him "the label of eccentric and lunatic from his contemporaries.” And that was when "lunatic" meant something! Dunton then joined, according to another biographer, “the ranks of anonymous mercenaries ...who filled the bookstalls with countless tracts of poorly written and badly printed political and religious invective.”*

If you really want to know more about Dunton, you can read his freely-available-on-the-Internet seven-hundred-page autobiography, Life and Errors of John Dunton, late citizen of London; written by himself in solitude. With an idea of a new life; wherein is shewn how he'd think, speak, and act, might he live over his days again, published in 1705. (One eighteenth-century critic compared Dunton's writing style to“tangled chain, nothing impaired, but all disordered," so you might want to skip it.)†

That's it for this go-round, Readers Mine. What curious bagatelle shall usher forth from the Cabinet next time? Only Your Oracular Author knows for sure!

_________________________________________________________

* From Stephen Parks's John Dunton and the English Book Trade.

† Or, you can read Gilbert D. McEwen's engaging biography of Dunton, The Oracle of the Coffee House (1972), if you live near one of the twelve libraries in the world that have a copy.

.jpg)