The Japanese ambassador to Pope Gregory XIII thanks him for his calendaric innovations.

Good day, regular, first-time, or begrudging readers. In commemoration of the recent Fall or Autumn Equinox, I bring you some interesting minutia on our favorite time-tracking device, the calendar! The word "calendar" comes from kalendae, which means "first day o' the month" in Latin.

Perhaps you have heard of the Gregorian calendar? Maybe you are even familiar with its machinations. It was developed as a chanted time-keeping system in Italian monasteries during the fifteenth century, under the auspices of Papa Gregorio XIII. There are twelve months, or, one for each Apostle. Each month was allotted thirty, thirty-one, twenty-eight, or twenty-nine days, according to the whim of His Holiness. Gregory developed a helpful mnemonic for his monastics to help make sense of this confusing system: "Dierum triginta habere September ..."

Confused sixteenth-century peasants debate the merits of the new Gregorian calendar.

Calendario Gregorio replaced the Julian calendar, personally designed by "July" Caesar to record his conquests and best name months himself. Developed post-Reformation, the Gregorian calendar was instantaneously adopted by Faithful Papist Countries, like Spain, Portugal, the Papal States, and that old warhorse, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Other states took longer to come around to this crazy new time-marker. Most Protestant nations, like the Netherlands and Denmark, feared that the calendar reform was an insidious Popish plot meant to draw them back to Mother Rome. (Which it was.) Most of Western Europe, except Britain, had come around by 1700, however.

Yes, the Island Race was as hesitant to adopt this Continental calendarical barminess and forsake the beloved Julian calendar as they are to adopt the Euro and scrap the ailing Pound Sterling. Britons hemmed and hawed until 1752, when a reluctant George II deigned to adopt the calendar used in his Hanoverian homeland since the turn of the eighteenth century.

"Give us our eleven days!":

Pandemonium broke out in Britain in 1752 for a fortnight but three because of the transition from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar. Unfortunately for the protesters, the changeover erased those very days from the annals of recorded time, and the souls of these poor wretches have been lost to history. (Painting by William Hogarth)

* * *

Pandemonium broke out in Britain in 1752 for a fortnight but three because of the transition from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar. Unfortunately for the protesters, the changeover erased those very days from the annals of recorded time, and the souls of these poor wretches have been lost to history. (Painting by William Hogarth)

The Glorious Fatherland Russian Empire, also known as Russia, loved their Julian calendar as much as they loved samovars and feudal slavery. By 1900, the Rus peoples had refused to adopt this new and radical calendar for centuries. It took a Julian-calendar-named revolution, the (Hunt for Red) October Revolution (which actually began on November 7th Gregorian) to usher in the new time-marker.

Even this capitalist bourgeois cat knows it is time to abandon the decadent Julian calendar. But first, fire up the samovar! (Painting by Boris Kustodiev, 1918)

* * *

But enough about this real calendar that everyone actually uses, what about Obscure and Antiquated Calendar Systems? Well, here are a few in all their inscrutable and exotic glory:

The Golden Hat calendar (shown below) was worn by Bronze Age (c. 1200-800 BCE) Germanic wizards to conjure accurate timekeeping systems for their amazed subjects. The bands and raised dots, among other ornaments, inspired these temporal whizzes to predict the right time to plant and reap their crops within their fifty-seven month calendar year. Also, they were damnably heavy.

The Positivist calender was a reform of the Gregorian calendar proposed in 1849 by French philosopher and proto-sociologist Isidore-Auguste-Marie-Francois-Xavier "IAMFX" Comte. The calendar was thought up by the so-called "bad Comte," who was, according to child supergenius, imperialist, and penpal John Stuart Mill, the evil counterpart to the "good Comte," inspiring friend R. L. Stevenson to write his famous novel-for-lads, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

The calendar had thirteen months of twenty-eight days, with a festival day, "Dia de los Muertos," added to bring the total to 365. Every day, week, and month was named after Famous Dead White Dudes, including the months of Aristotle, Shakespeare, Dante, and Moses. Perplexing why this didn't spread like wildfire, as his Religion of Humanity did.

The calendar had thirteen months of twenty-eight days, with a festival day, "Dia de los Muertos," added to bring the total to 365. Every day, week, and month was named after Famous Dead White Dudes, including the months of Aristotle, Shakespeare, Dante, and Moses. Perplexing why this didn't spread like wildfire, as his Religion of Humanity did.

An earlier French stab at calendar-re-imagination was much more sensible. The French Republican Calendar, used from 1793-1805, consisted of twelve months divided into three ten-day weeks, or décades. The tenth day of each week was the new Sabbath of Reason. The leftover days needed to approximate the solar year were herded at the end of each year, during which a raging Liberty Party was caused to be thrown.

Each day was furthermore divided into ten hours, each hour into 100 decimal minutes, and each decimal minute into 100 decimal seconds. This metric time was not widely embraced, however, as Le Metre, Le Gram, and other dumb metric junk they tried to make us learn in grade school was. The months had wonderfully quaint seasonal names (not useful in tropical climes, it would seem), like "Grape Harvest," "Fog," and "Summer Heat." Days, formerly named after saints, were now called agricultural things like: "Potato"; "Wine Press"; "Shovel"; and "Pig."

Each day was furthermore divided into ten hours, each hour into 100 decimal minutes, and each decimal minute into 100 decimal seconds. This metric time was not widely embraced, however, as Le Metre, Le Gram, and other dumb metric junk they tried to make us learn in grade school was. The months had wonderfully quaint seasonal names (not useful in tropical climes, it would seem), like "Grape Harvest," "Fog," and "Summer Heat." Days, formerly named after saints, were now called agricultural things like: "Potato"; "Wine Press"; "Shovel"; and "Pig."

A "Republican Clock," complete with funny French Revolution hat, cannon, and Tricolor.

The Old Icelandic lunar calendar, which evolved from the Viking calendar, was divided into twelve months of two six-month "seasons": "Short Days" and "Nightless Days" (also not useful in the Tropics). Each month began on the same day of the week. Months had evocative names like "Fat-Sucking Month" and "Hay Business Month." This calendar was used from the ninth century until 1945 (maybe).

The Althing(s to Allmen), the Icelandic parliament, meeting, as usual, on a seaside cliff, discusses the implementation of the Gregorian calendar after Iceland's rediscovery by Norway in 1905.

But what about other, non-European calendars, you Eurocentric old white dude? Let's take the Wayback Machine all the way back to Ancient Babylonia (around 4,500 years ago). The Babylonian calendar is a lunar one, with twelve months of twenty-nine or thirty days, with an extra month inserted as needed, at the discretion of dudes like Gilgamesh d'Ur, Sargon von Akkad, Hammurabi the Coder, and Nimrod, when he wasn't out hunting.

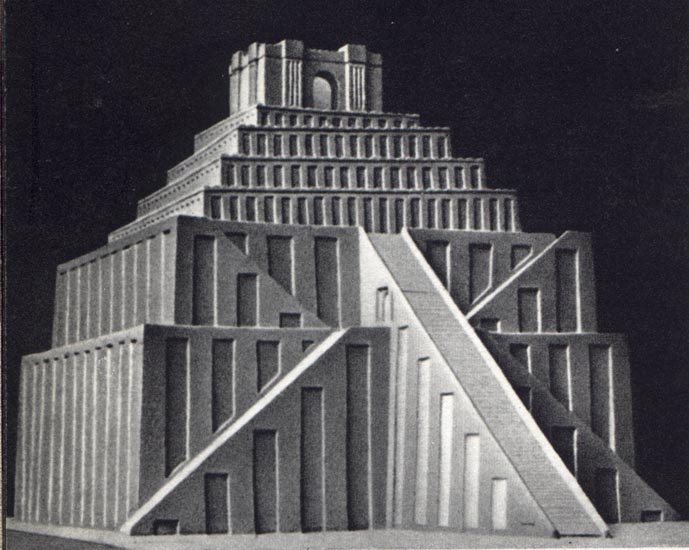

Perhaps you will be familiar with the Babylonian seven-day week, with the ultimate day called an "evil-day," during which one was encouraged to pray to Ishtar, Marduck, and their lot, while refraining from unholy activities. On this day, commoners, for example, were not allowed to "make a wish," an activity they resumed in great earnest the following day, "Blue Moonday." The final day of the month was a day of rest from all that Cuneiforming and infant-sacrificing and hanging-gardening. These days began at sunset, or, rather, moonrise. Adolescents apprenticed in the craft moonspotting were stationed at every convenient ziggurat to proclaim the dawn of the new day.

Fun fact: because of the Jewish Babylonian exile, it is the basis for the Hebrew calendar that is still in use. The months, many originally named after Babylonian deities, were kept in altered form for the Hebrew calender.

Perhaps you will be familiar with the Babylonian seven-day week, with the ultimate day called an "evil-day," during which one was encouraged to pray to Ishtar, Marduck, and their lot, while refraining from unholy activities. On this day, commoners, for example, were not allowed to "make a wish," an activity they resumed in great earnest the following day, "Blue Moonday." The final day of the month was a day of rest from all that Cuneiforming and infant-sacrificing and hanging-gardening. These days began at sunset, or, rather, moonrise. Adolescents apprenticed in the craft moonspotting were stationed at every convenient ziggurat to proclaim the dawn of the new day.

Fun fact: because of the Jewish Babylonian exile, it is the basis for the Hebrew calendar that is still in use. The months, many originally named after Babylonian deities, were kept in altered form for the Hebrew calender.

At the apex of the ziggurat, apprentice, journeyman, and master moon-spotters awaited the dawn of a new day. They were perplexed and disappointed every 29.53 days. :(

* * *

Well, I'm afraid that's all the time we have here at the Cabinet. I hope to return within a fortnight to bring you fresh curiosities and novel oddities for your electronic-reading pleasure.