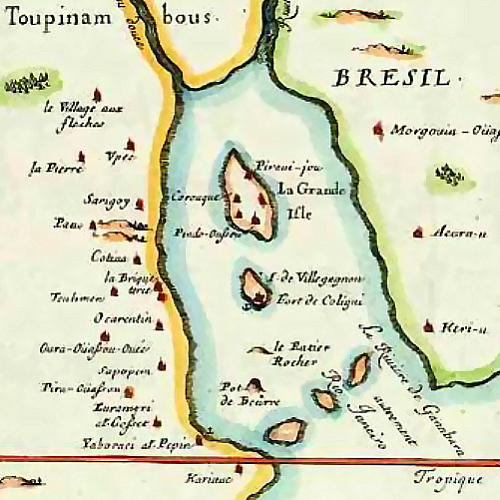

Map of South America, 1575, from Thévet,

with France Antarctique highlighted for your convenience!

(Whoa, ship, watch out for that bonfire smoke blowing in from Antarctica!)

With the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics fast approaching, Your Humble Wordsmith thinks it high time for a Rio de Janeiro (pseudo-) history lesson. Yes, that Rio, home of great mountains mined for sugar, one-name soccer stars, Duran Duran hits, girls from Ipanema, and critically-acclaimed slum drug wars.

Perhaps you also know the land of Brazil to be a Portuguese-speaking nation and giant former colony of Portugal (1500-1815). But one of the first European settlements in Brazil, indeed one located where the modern city of RDJ thrives, was a French colony, France Antarctique, or, "Antarctic France"!*

Antartique-booster King Henri II (L) and colonial impresario Villegagnon (R)

In the sixteenth century ("the 1500s"), France was burgeoning European power but was a nation riven with Reformation-caused religious wars, pitting Catholiques ("Papists") against Huguenots ("Heretics"). Nicolas Durand de Villegagnon (1510-71), a naval officer, sympathized with the Huguenots, and desired to find them a colonial refuge far from France. He enlisted the support of French king Henri ("Henry") II, noted burner of Protestants, who wanted to dump the Huguenots on another continent, and several Huguenot-leaning aristocrats, to bankroll the enterprise.

Sailing with two ships and 600 probably desperate and largely Protestant colonists in November 1555, Villegagnon made for Guanabara Bay in Brazil. According to historian Francis Parkman, there were also "young nobles, restless, idle, and poor, with reckless artisans and piratical Norman and Breton sailors" among the ranks. Which is to say, a couple of ships full of dudes.

Location of the French settlement in modern-day Rio de Janeiro.

[Photograph by the author.]

Their destination was a bit problematic. The Pope had divided the non-European world between Spain and Portugal in the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494. Also, a Portuguese fleet under Pedro Álvares Cabral had literally run into Brazil, probably by accident, in 1500 on its way to Africa and the East Indies. Portugal had established settlements, São Vicente, by the 1530s. But the French had been clandestinely raiding the coast for years to harvest the lucrative native Pau-brasil, or Brazilwood (not to be confused with Brazil nuts!), using its red wood for textile dyes back in France. Where else would famed musketeer-menace Cardinal Richelieu get his signature threads?

After landing and immediately celebrating mass (see above), the settlers chose an island, called Serigipe by the local Indians, to stake their claim. Here they built a fort they named Fort Coligny, after famous Huguenot and colony-bankroller Admiral Gaspard "Sounds Like 'Colony'" de Coligny. The fort was your run-of-the-mill wood-pike and earthwork model (see Jamestown, Virginia). They planned a more permanent settlement on the nearby mainland, which Villegagnon christened "Henriville" after their Protestant-loathing patron, Le Roy. (Unfortunately, some people called the native inhabitants already lived there.)

A rather less accurate depiction of Guanabara Bay, from 1555.

Villegagnon made an alliance with the local Tupi Indians against the Portuguese. Too bad Our Dear Leader Villeganon treated his colonists like dirt, flogging and starving them at his whim. He soon had a change of religious heart, as many Frenchmen did in those days, and went back to Catholicism, problematic in a majority-Protestant settlement.

An additional three ships with 300 virgin colonists (including at least five women and a nun!) arrived two years later, in 1557. Among them were some pretty zealous Huguenot Calvinist priests, with which Villegagnon had a rather messy falling out. He eventually banished them, first to the mainland, then to France, and they sailed back to Europe without any food or supplies. Villegagon, the new Catholic, was fed up and went back to France soon afterward, but not before he flogged and exiled several more colonists.

A Brazilwood tree, probably the real reason for French colonization,

in modern-day Henriville Rio de Janeiro.

By 1560, the Portuguese had realized the French were hanging out in their colony, and the fact that they were Protestant French probably made them even more angry. They assembled a fleet of twenty-six warships to reclaim Guanabara Bay and kick out the Huguenots. After three days, the Portuguese, led my the new governor of Brazil, the wonderfully-named Mem de Sá, had destroyed the fort but failed to exterminate the colonists, who, with the help of their Tupi allies, had escaped to the mainland. Mem's nephew, Estácio de Sá, founded Rio de Janeiro nearby in 1565, but the French settlers continued to awkwardly hang around until 1567, when Estácio and the Portuguese finally drove them out (probably they intermarried with the natives or were just all murdered). And so the dream of "France Down Under" came to an end.

"Geneva in the Wildnerness," as John Calvin liked to call it.

The Ile-de-Villegagnon, 1560, being attacked by Mem and his fleet.

But FA had caused a continued French fascination with things Brazil. (There would be another failed colonization attempt in the 1610s, the similarly-named France Equinoxiale.) The failed experiment also spawned several accounts of the settlement, its flora and fauna, and its native inhabitants.

Among the first gaggle of Protestant colonists was the Franciscan priest André Thévet (1516-90), acting as the Father Mulcahy of Villegagnon's fleet. He wrote up his observations on Brazil's natural history and peoples in his book The Singularities of Antarctic France (1558). He was the first guy in France to write up observations of native plants like pineapples and tobacco. Another colonist, the Huguenot minister Jean de Léry (1536-1613), wrote up his experiences in History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Also Called America (1578)

Both of these accounts were lavishly illustrated, and several are reproduced below:

André Thévet (R), well-known tiny-globe-collector and Brazilophile,

and Jean de Léry's 1578 Brazilian travelogue (R).

A demon-eyed toucan, known for attacking French colonists with its murderous beak.

Brazilian natives regularly invited their new neighbors to weekend backyard barbecues.

(From Thévet)

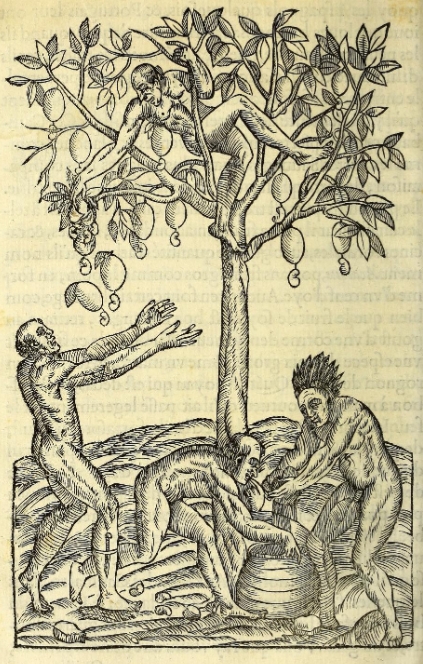

Natives harvest cashew fruits (top) to produce large pots of mixed nuts (bottom).

(From Thévet)

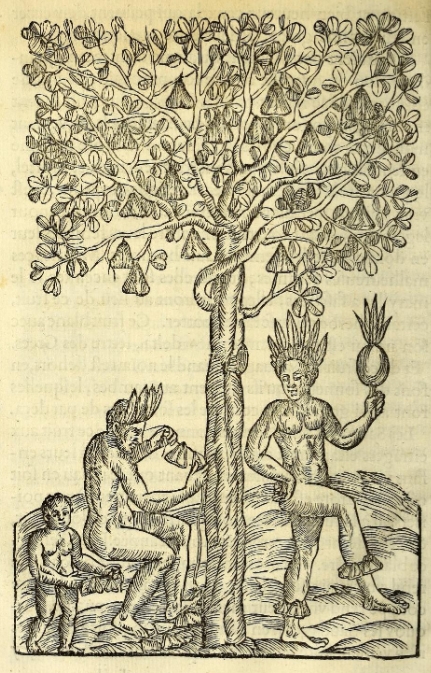

A native chief twirls a pineapple on his finger, Globetrotter-style,

while his fellow tribesmen look distracted.

(From Thévet)

I have no idea what is going on here. But my sources tell me the the intellegent-faced beast is supposed to be that Brazilian native, the sloth.

(From Thévet)

"How the Amazons treat those they take in war." Watch out, French settlers!

(From Thévet)

"People [naked slaves?] cut and carry Brazilwood for ships."

(From Thévet)

"An Indian Family," just hanging out with a pineapple. (From de Léry)

"Portrait of the battle between the Tupinamba Indians and Margaias(?) Americans."

Native Brazilians war as a disinterested parrott (far right) looks on, the locals barbecue some limbs (top-left), and a draft-dodger naps in a hammock (top-center)

(From de Léry)

"Evil spirits, called 'Aygnan', tormenting the Indians of Brazil,"

Note the return of the wise but enigmatic man-faced beast (middle-left), standing next to the Frenchmen chewing the fat with a native (middle-center), while an evil spirit is tenderly comforting (or devouring the soul of) a man (bottom-center).

(From de Léry)

Well, Treasured Readers, after these jolly scenes, we have come to the end of another edition of the Cabinet. May you avoid ambushes by evil spirits and have the good fortune to stumble upon a learned and kind man-sloth in your travels!

______________________________________________-

* No happy-footed penguins or retreating ice sheets in this Antarctic! For some reason, the French called the whole area south of the equator the Antarctic ("opposite of the Bear").