Left: A 1617 engraving of Richard Whittington by Renold Elstracke (National Portrait Gallery, London). A printer altered the engraving, originally showing Whittington holding a skull, to include his famous cat.

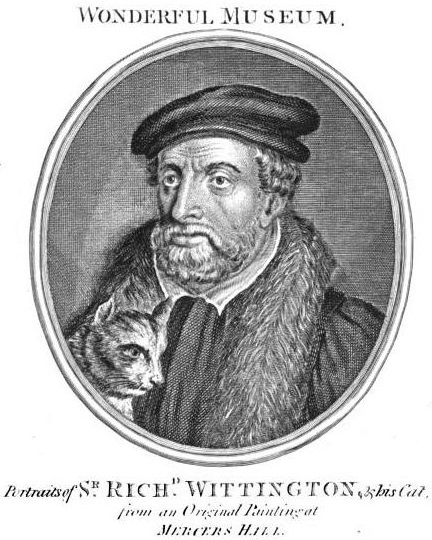

Right: "Portraits of Sir Richard Wittington and his Cat, from an Original Painting at Mercers Hall" (From The Wonderful Museum, 1808).

Hello! Perhaps you thought I had abandoned you, Gentle Readers, because of my lengthy absence from this Forum of Rarefied Discourse. Or maybe you didn't even notice, but no matter - your Prodigal Blogger has returned!

Today, I bring you the tale, long promised but hardly expected, of the legendary professional cat-fancier Sir Richard Whittington (1354-1423), four-time Lord Mayor of London and Member of Parliament, Knight of the Realm, etc., etc. A generous, charitable man, upon his death, his vast fortune went to the foundation of the Charity of Sir Richard Whittington, which operates to this day.

Too bad a heartwarming and possibly magical feline friend he purportedly owned as a boy obscures these actual achievements and good deeds! The legend, bandied about in England's pleasant pastures green since the fifteenth century, runs thus:

Dick (Richard Whittington) is an impoverished orphan boy from Gloucestershire in the English countryside. Making his way picaresquely to the "gold-paved" streets of the Capital, London, Dick finds not gilded metropolitan pavers but only more hard times.

Dick, dressed smartly in Merry Man attire, rests his bindle on the road to London.

(From Flora Annie Webster Steel's English Fairy Tales, 1918.)

Taken in by a wealthy merchant, a certain Fitzwarren ("Bastard son of some guy named Warren"), Dick gains employment as a servant but also discovers his quarters are infested with rodents. [Ed.: Bubonic Plague a-comin'!] What can a poor boy do?

To combat this pestilence, Dick buys a cat with his meager earnings. [Ed.: Did one really have to BUY cats during the Middle Ages? I could walk outside my home right now and get one for free!] Seemingly the cat rid Dick's hovel of rodents, or at least left his room scattered with dead mice.

Dick shows off new his cat to some people in snazzy, fabric-heavy clothes (presumably Fitzwarren and his daughter Alice). As our hero would soon discover, girls love men with wealth-producing cats.

Yet Dick inexplicably donates his cat to a ship that his cruel master "Bastard" Fitzwarren is sending on a trading expedition to the Barbary States of North Africa. Everyone in the Fitzy household is expected to contribute something to trade for gold, and the cat is judged Dick's only possession that a Berber might want. After several more months under the boot of Mr. Fitzwarren and his malevolent servants, Dick decides to run away from his job and from London. But, before he can, he hears some magical church bells (from St. Mary-le-Bow) that seem to say, "Turn again Whittington, thrice Lord Mayor of London." Catchy!

Running back to Fitzwarren's, he discovers that the trading ship had returned. Moreover, his nameless cat had been sold to the King of Barbary for a fortune in gold, because the palace was overrun my mice! Now possessing a fortune, because Fitzwarren inexplicably gave all the gold from a trading venture he solely financed directly to a boy, without taking a cut, Dick was rolling in Pounds Sterling!

The Celebrated Cat proves his merit for an assembly of rodent-pestered Barbary worthies dining on the eastern delicacies lobster and pumpkin.

(From Steel.)

Fitzy decides to take on the capital-rich Dick as a junior partner and son-in-law, marrying him off to his daughter, Alice Fitzwarren (his real-life wife!). Dick lived happily ever and anon, becoming, just as the bells had prophesied, Lord Mayor of London (a posh appointment, both then and now) three times. ----- THE END!

It's not a very good story, truth be told, but I'm sure you figured that out already. It wouldn't even have passed as a Canterbury Tale, I think. Yet, despite its lack of narrative merit, early modern storytellers often used it as a basic framework for Aristocrats-style ("Aristocats"?) comical tales, and many musical pantomimes and Punch-and-Judy-type shows of varying content and quality were based on the legend.

A play appeared in 1604 called The History of Richard Whittington, of his lowe byrth, his great fortune, and was a theatrical success to rival contemporary productions of Othello and Hamlet. Puppet acts starring Whittington & Cat probably developed because of the play's popularity. No other than the graphomaniacal diarist Samuel Pepys (PEEPS) recorded that he "saw the puppet show of Whittington, which was pretty to see" at the "very dirty" Southwark Fair.

The first pantomime version appeared in 1814, and many others appeared as the story was embellished and refined over the Victorian age, including Dick Whittington and His Cat; Or, Harlequin Beau Bell, Gog and Magog, and the Rats of Rat Castle, by Frank Green and Sidney Davis. The young theater critic George Bernard Shaw, writing for the Era, said that the production "[is] all life, bustle, briskness, brightness, beauty. There are sweet sounds for your ears, pretty pictures for your eyes, and no end of comicality to make exactions upon your risible faculties." Of course, he wrote almost exactly the same thing about Ibsen's play A Doll's House several years later.

The real Whittington was born into gentility, and there is no evidence he ever owned a cat. So, where did the legend originate? The lazy (and correct) answer is that scholars still aren't sure (how surprising!). The folktale may be derived from a Persian story from the thirteenth century, and the legend of an orphan gaining fame and fortune through his cat was current in most of Europe during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Why it was so popular and enduring a story is anyone's guess, am I right?

Oh! to be a really skillful courtier and politician, but only to be remembered for the feline friend you never even had! Such is the cruelty of history, my friends. The tyranny of popular memory triumphs over historical fact! Or at least that's what I would have said in my graduate school term paper. And on that note, Dear Readers, I close the Cabinet until I next summon open its creaky doors.