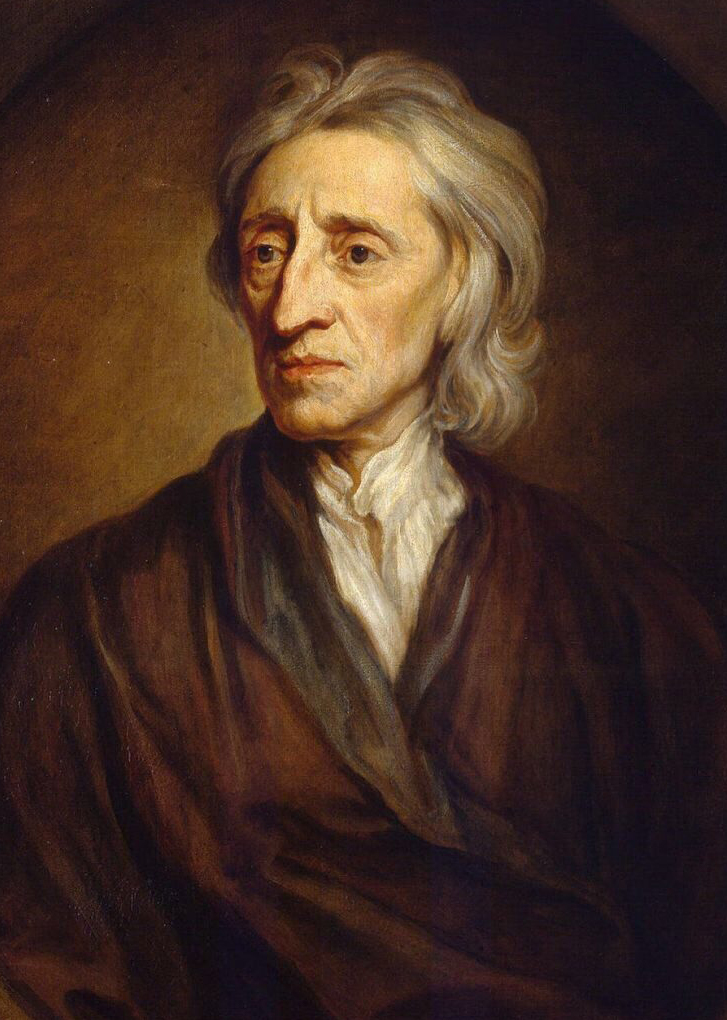

A modest man, Washington prays in 1778 at Valley Forge that the unpopularity of biography in the English-speaking world during most of the eighteenth century will continue after his death. He didn't know that he needed to worry about commemorative stamps, too!

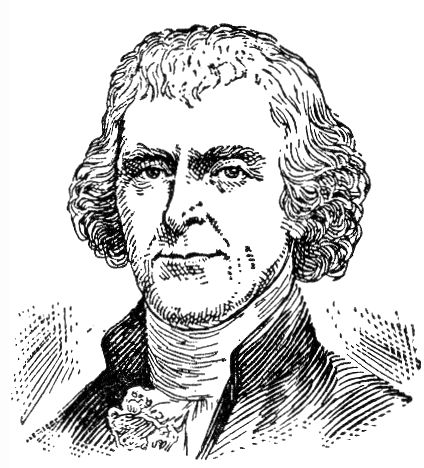

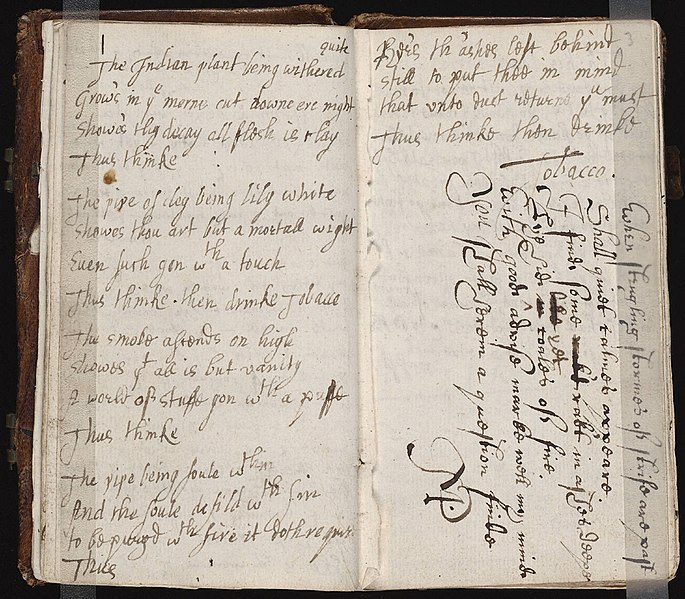

From T. Woodrow Wilson's biography George Washington -- p. 1 (L) and an illustration of Washington's favorite Colonial Williamsburg hangout, then called the New Raleigh Tavern (R)

But these two men were not just Versailles-Treaty-wrangling rivals. It is a little-known but extremely important fact that both men, in their salad days, wrote lengthy biographies of the man first in war, first in peace, and first in the heart of amateur biographers -- George "His High Mightiness" Washington! Following in the great tradition of Mason Locke "Parson Weems" Weems, Wilson's biography, the cleverly-titled George Washington, appeared in 1896, while Lodge's work, uniquely called George Washington, was published in 1889.

Henry Cabot Lodge relates the story of the young Washington, who, when accused of illegally surveying the neighboring estate, told his elder half-brother Lawrence, "I cannot tell a lie. I am participating in the secret initiation rite of the Junior Freemasons of Stafford County."

Lodge, heir to a vast hotelier fortune, was great pals with Theodore "The Dutch Waashington" Roosevelt, and the two even coauthored the scholarly tome Hero Tales from American History (1895). He was qualified, too, holding the first Ph.D. granted in political science from John Harvard University, studying with fellow American aristocrat Henry "Autobiography" Adams.

Wilson, too, was a qualified biographer, holding a Ph.D. in history and political science from The Johns Hopkins Brothers University in Baltimore, Mary-Land, and working as a professor at several universities, including his undergraduate alma mater, the State University of New Jersey at Princeton.

It must be noted that all three men were FREEMASONS. It is no coincidence that Wilson called his plans postwar Europe the "New World Order." It was rumored that, during their public argument over the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, Wilson and Lodge engaged in a secret fist-fighting match in front of their fellow Congressomasons on the very ground outside of Washington, D.C. on which the George Washington Masonic National Memorial obelisk-lighthouse and gift shop would be built only a few years later!

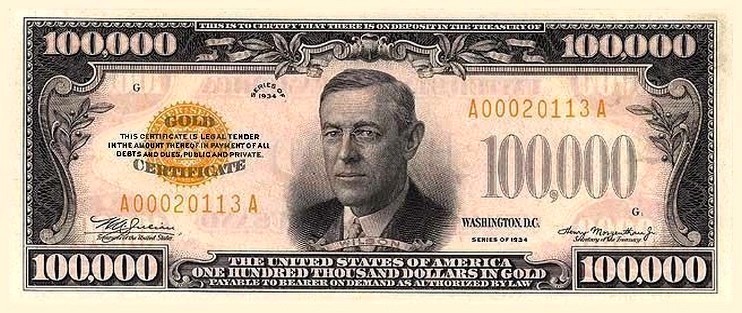

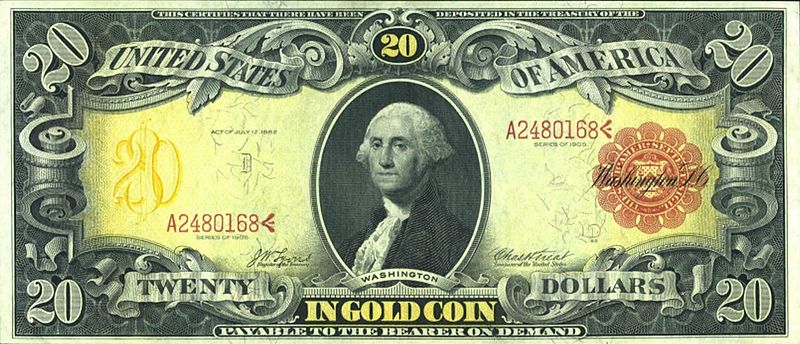

Was it a coincidence--or fate?!?--that the presidential visages of both Wilson and Washington graced denominations of U.S. Gold Certificates? (Wilson, strangely enough, demanded of his publisher, Harper & Bros., now HarperCollins, that he only be paid in gold coin put in plain canvas bags with dollar signs on them.)

Lodge, who only dreamt of appearing on U.S. legal tender. With this futile hope, he commissioned this engraving:

But what of the actual biographies themselves? Were Lodge and Wilson nineteenth-century masters of muscular prose, or mollycoddling stylistic featherweights? Let's go to the source!

Wilson (a Virginian) begins his book thus:

George Washington was bred a gentleman and a man of honor in the free school of Virginian society. He came to his first manhood upon the first stir of revolutionary events; caught in their movement, he served a rough apprenticeship in arms at the thick of the French and Indian War; the Revolution found him a leader and veteran in affairs at forty-four; every turn of fortune confirmed him in his executive habit of foresight and mastery; death spared him stalwart and commanding, until, his rising career rounded and complete, no man doubted him the first character of his age.

Virginia gave us this imperial man, and with him a companion race of statesmen and masters in affairs. It was her natural gift, the times and her character being what they were, and Washington's life showed the whole process of breeding by which she conceived so great a generosity in manliness and public spirit.Compare it to the end of the introductory chapter from Lodge (a Yank):

Behind the popular myths, behind the statuesque figure of the orator and the preacher, behind the general and the president of the historian, there was a strong vigorous man in whose veins ran warm red blood, in whose heart were stormy passions and deep sympathy for humanity, in whose brain were far reaching thoughts, and who was informed throughout his being with a resistless will.

The veil of his silence is not often lifted, and never intentionally, but now and then there is a glimpse behind it; and in stray sentences and in little incidents strenuously gathered together; above all in the right interpretation of the words and the deeds and the true history known to all men, -- we can surely find George Washington, the noblest figure that ever stood in the forefront of a nation's life.

These passages left me with a burning question--will we ever enjoy another semicolon renaissance in our fair nation? Even graduate school in the humanities, that last bastion of overwrought prose, is abandoning its use; like Washington, I fear we shall never see its likes again.

Yet I digress; both authors celebrate the masculine virility of Washington; Wilson emphasizes his gentlemanly nature and his superior breeding; Lodge, however, finds inspiration in Washington's "stormy passions" and "resistless will." I think I know which one hung out with Teddy "Big Stick" Roosevelt!

So what do these Progressive politicians contribute to our understanding of Washington? What do they tell us that Weems, Washington Irving, Ron Chernow, Richard Brookheiser, Joseph Ellis, William Roscoe Thayer, David Ramsay, Charles Cooper King, Eugene "Weems" Parson, Horace Elisha Scudder, William Osborn Stoddard, John Stevens Cabot Abbott, Norman Hapgood, Bushrod "Actual Relative" Washington, Paul Leicester Ford, Jared Sparks, and your mom haven't said? Nothing, really. But making that list was good fun!

Martha Washington, dedicat'd Ockultist, reading Weems' biography.

Ultimately, as Jill "Blindspot" Lepore recently wrote in the New Yorker, Washington wasn't really that interesting anyway. Beyond his slave-teeth dentures and giant pot farm, Washington was just another un-college-educated Virginia patriarch with a faux-stone mansion facing the Potomac. Perhaps Lodge and Wilson, as both historians and politicians, felt that they must deal with the legacy of Gentleman George before they embarked on careers in the public eye.

Or perhaps it was part of a Masonic initiation rite, in which all new members had to write a biography of a prominent former member. Or maybe, just maybe, it was a coincidence. But, as George's wife Martha was fond of saying, "In the magickal Universe, there are no Coincidences, and there are no Accidents; nothing happens unless Someone wills it to happen."

_445.jpg/433px-Die_Gartenlaube_(1876)_445.jpg)