In the South Seas: Robert Louis Stevenson (center, seated) and The Family at his house Vailima, on the island of Upolu in Samoa. The skirted man on the right is fellow the Polynesian transplant and noted moocher Paul Gauguin, today best known for his innovative reforms of the Parisian stock exchange.

"The South Sea Islands," eighteenth-century wit Samuel Johnson once quipped during one of his famous "Quote-Off" garden parties, "are only fit, for Shyster joint-stock Company Speculators, and for the Scots." As always, the Good Doctor was at least 40 per cent. correct. Few Britons of Johnson's generation traveled to the far-flung climes of the South Seas, modern-day Polynesia. But, by the late nineteenth century, divers and sundry pale-and-wan-types were steamer-tramping their way to the newly-imperialized islands of the south Pacific. The mustachioed professional author and dyspeptic Robert Louis Stevenson was one such consumptive, a condition perhaps to blame on his adolescence in the miserable climes of Scotland. Finding San Francisco, his first escape, too clogged with polluted places of disrepute, like denim factories, Chinese laundromats, and tenderloin stands, Stevenson packed up his wife, Fanny, and their imaginary children in 1888 for a maritime journey to the sun-kissed Antipodes.

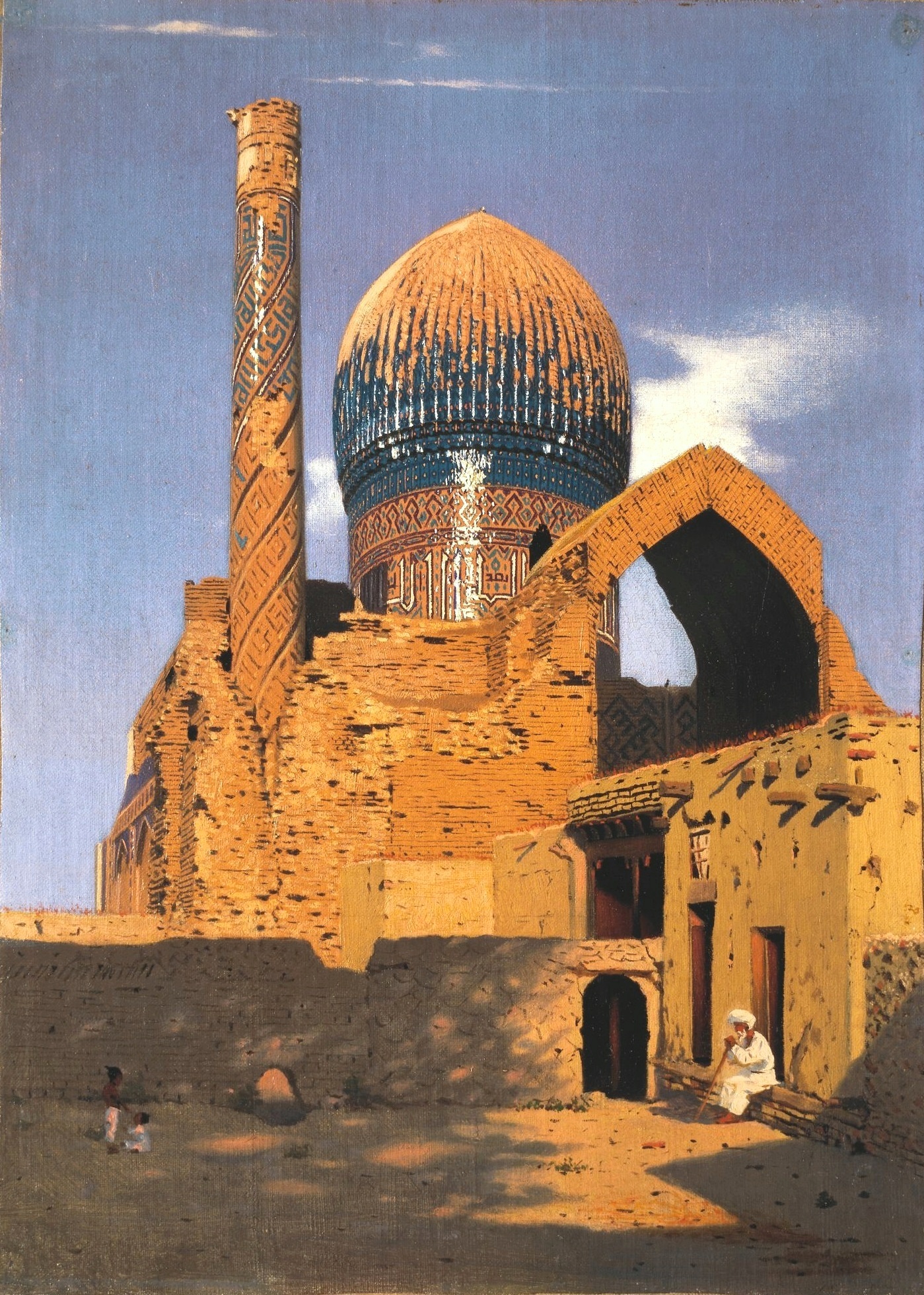

He left his consumptive condition in San Francisco: A contemporary hand-colored photograph of the house Stevenson and his family left behind in Monterrey, California. As you might be able to tell from the condition of the house, Stevenson's efforts at gold prospecting on the nearby American River were at least forty years late and several Pounds Sterling short.

Stevenson traveled to the Marquesas, Tahiti, Samoa, and Hawai'i before settling permanently in Samoa. He chronicled his experiences in several books and essays, churning out In the South Seas, A Footnote to History: Eight Years of Trouble in Samoa, and Polynesia on 40 Shillings a Fortnight, in addition to several short stories set in the South Pacific, during his six years there.

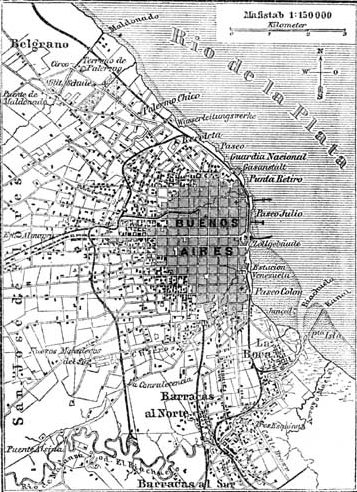

Stevenson's hand-drawn map of Samoa: Because he feared that steamship fumes would aggravate his distemper, Stevenson forced his family to travel from San Francisco to Samoa in an antiquated galleon, the Mentiroso, that still operated out of Manilla (pictured lower left).

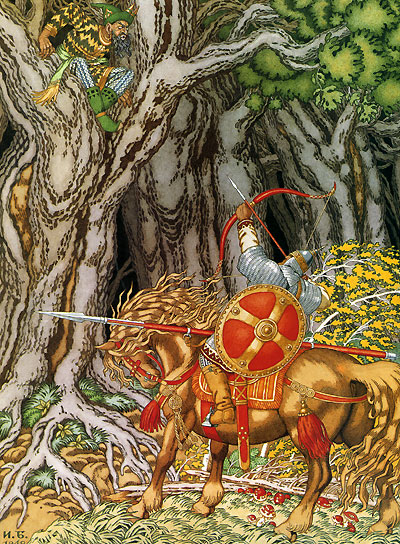

R. L. hanging out with his favorite Polynesian monarch, King Kalakaua of Hawai'i, 1889: It is thought that a mutual respect for mustaches was the catalyst for their lasting friendship. In respect for an ancient Hawaiian custom, Stevenson never made direct eye contact with the native sovereign during their meetings.

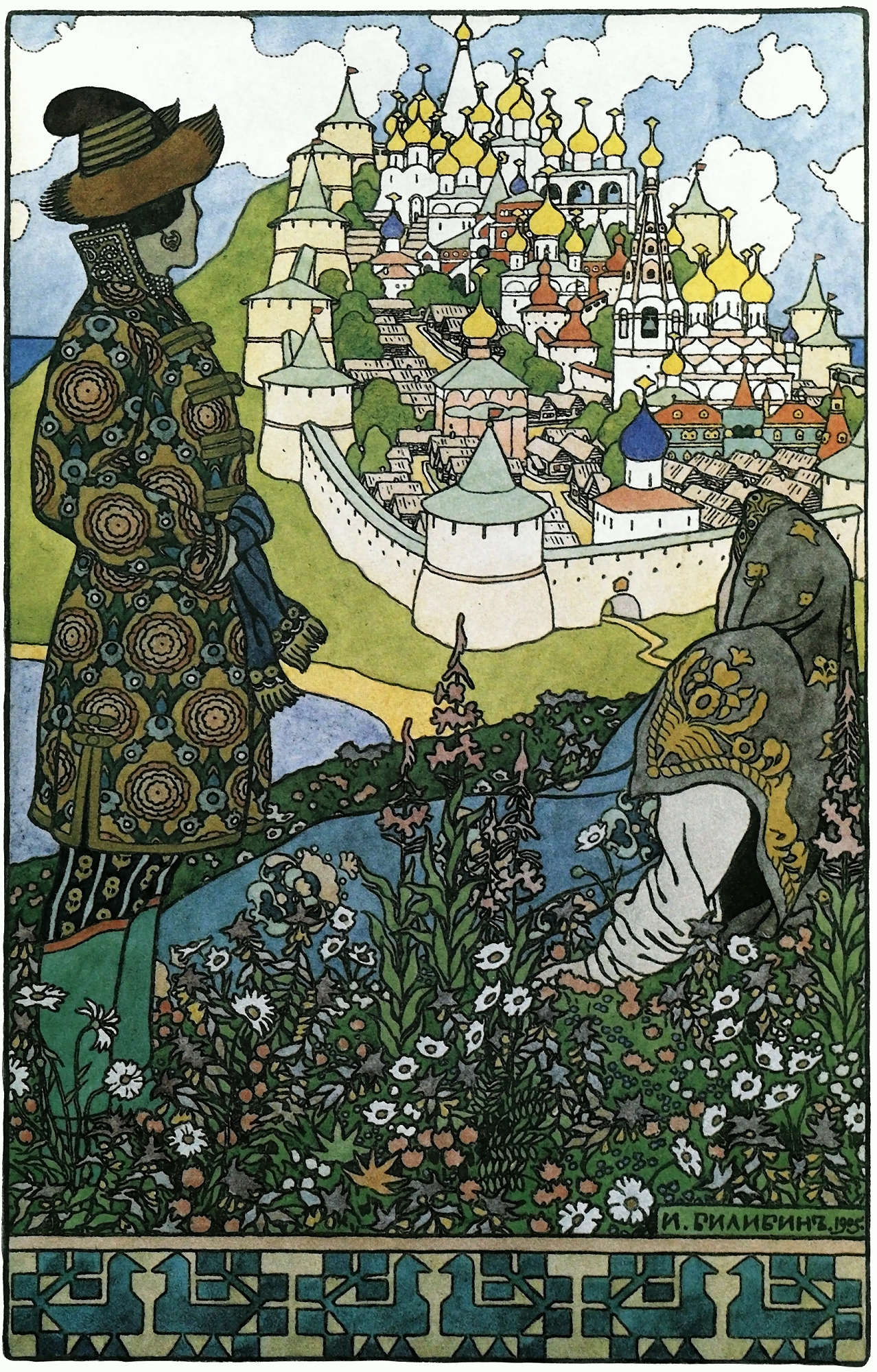

For He's a Jolly Good Roger: A commemorative print sold in Edinburgh of Stevenson's welcome by the people of Samoa. Although this engraving is an accurate representation of the events, all participating are clothed inappropriately. The usually half-naked Samoan women seemingly have adopted modified togas, while RLS himself would have burned alive in that formal wool suit. But I realize that I am a Zealot for period clothing accuracy.

Stevenson paid four thousand dollars for a three-hundred-acre estate on an up-island plateau. Here, in 1890, he built his two-story and bi-veranded house, which he called Vailima, Samoan for "poorly informed real estate transaction." Great fans of his novels and short stories, the local Samoan chiefs called Stevenson "Tusitala, Teller of Tales," and the Scot enjoyed commissioning giant outrigger canoes from his neighbors.

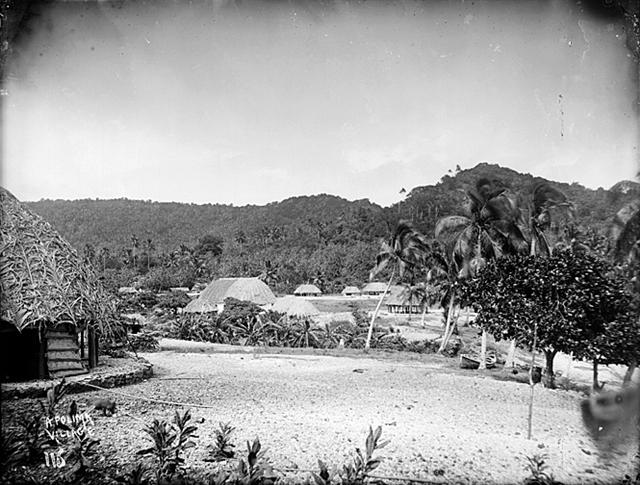

A Samoan village, c. 1890: The hut-like building on the left is one of the first now-infamous confectionery factories in the islands, commissioned by Juliette Gordon Low for her new girls' paramilitary organization.

Robert and Fanny lived happily, if platonically, at Vailima for several years. Stevenson's health and his "chronic gauntness" never did fully recover, however, and he died at the end of 1894 at the age of forty-four. His chief-friends buried him on the top of Mt. Vaea, the peak behind Vailima. Today, on his tomb, there a the worn inscription that I think qualifies for Ten Best Literary Epitaphs of the Nineteenth Century:

Vailima: Now apparently property of the United States government (note the stars 'n' stripes).